Scripts: Difference between revisions

(Some more english translation) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 75: | Line 75: | ||

* {{incode|import FreeCAD}} This line import FreeCAD in the FreeCAD Python interpreter, it may seem a redundant thing, but it isn't |

* {{incode|import FreeCAD}} This line import FreeCAD in the FreeCAD Python interpreter, it may seem a redundant thing, but it isn't |

||

* {{incode|from FreeCAD import Base, Vector}} Base and Vector are widely used in FreeCAD scipting, import them in this manner will save you to invoke them with {{incode|FreeCAD.Vector}} or {{incode|FreeCAD.Base}} instead of {{incode|Base}} or {{incode|Vector}}, this will save many |

* {{incode|from FreeCAD import Base, Vector}} Base and Vector are widely used in FreeCAD scipting, import them in this manner will save you to invoke them with {{incode|FreeCAD.Vector}} or {{incode|FreeCAD.Base}} instead of {{incode|Base}} or {{incode|Vector}}, this will save many keystrokes and make codelines much smaller. |

||

| Line 101: | Line 101: | ||

Put these lines after the "template" code and press the green arrow in the '''Macro toolbar''' |

Put these lines after the "template" code and press the green arrow in the '''Macro toolbar''' |

||

You will see some magic things, a new document is open named "Pippo" ( |

You will see some magic things, a new document is open named "Pippo" (Italian name of '''Goofy''') and you will see in the 3d view a cube, like the one in the image below. |

||

[[File:Cubo.png|thumb|center|Cubo di prova]] |

[[File:Cubo.png|thumb|center|Cubo di prova]] |

||

== |

== Something more... == |

||

Not too amazing? Yes, but we have to start somewhere, same thing we can do with a Cylinder, add these lines of code after the {{incode|cubo(}} method and before the line {{incode|obj = cubo(...'}}. |

|||

{{Code|code= |

{{Code|code= |

||

| Line 123: | Line 123: | ||

Even here nothig too exciting. But please note some peculiarities: |

|||

Anche qui nulla di eccezionale, notiamo alcune cose nella costruzione del codice: |

|||

* The absence of the usual reference to the {{incode|App.}}, present in many Documentation code snippets, is deliberate, this code could be used even invoking FreeCAD as a module in an external Python, the thing is not easily doable with an AppImage, but with some care it could be done. Plus in the standard Python motto that "better explicit than implicit" {{incode|App.}} is explaining in a very "poor" way where the things are from. |

|||

* L'assenza dei riferimenti usuali in molta documentazione ad {{incode|App.}}, è pienamente voluto, in futuro si potrà riusare il codice per accedere a FreeCAD dall'esterno di FreeCAD, e sarà necessario importare FreeCAD come un normale modulo Python, con alcune accortezze. La scelta è voluta anche nel solco degli standard di Python per cui è meglio sapere sempre da dove arrivano le cose, ovviamente App è poco significativo. |

|||

* {{incode|DOC = FreeCAD.activeDocument()}}, note the use of the "constant" name assigned to the active Document, that is not a "constant" in a strict mean, but in a "semantical" way is our "active Document", that four our use is a proper "constant" so the Python convention to use the "ALL CAPS" name for "constants", not to mention that {{incode|DOC}} is much shorten than {{incode|FreeCAD.activeDocument()}}. |

|||

* La definizione all'inizio di una "costante" DOC, per contenere {{incode|FreeCAD.activeDocument()}}, ovviamente il nome "costante" è solo considerando dal punto di vista semantico il nostro "documento attivo", da qui l'uso della convenzione del nome "TUTTO MAIUSCOLO" per le "costanti". |

|||

* every method returns a geometry, this became clear in the continuation of the page. |

|||

* ogni metodo ritorna un geometria, questo diventerà importante fra poco. |

|||

* |

* geometry didn't have the {{incode|Placement}} property, when usign the simple geometries to make more complex geometry, managing {{incode|Placement}} is a ankward thing. |

||

Ora dobbiamo pur farci qualcosa con questi oggetti, quindi introduciamo le operazioni booleane. Un esempio di metodo che compie un'operazione di '''Unione''' è questo: |

Ora dobbiamo pur farci qualcosa con questi oggetti, quindi introduciamo le operazioni booleane. Un esempio di metodo che compie un'operazione di '''Unione''' è questo: |

||

Revision as of 10:56, 3 March 2020

Editing Scripts

Work in progress sorry for the inconvenience

With Scripting we mean create topological objects using FreeCAD Python interpreter. FreeCAD could be used a "very good" replacement of OpenSCAD, manìinly beacause it has a real Python interpreter, that means that it has a real programming language on board, almost everything you could do with the GUI, is doable with a Python Script.

Sadly information about scripting in the documentation, and even in this wiki are scattered around and lacks of "writing" uniformity and most of them are explained in a too technical manner.

Wetting you appetite

The first obstacle in an easy way to scripting is that there is no direct way to access the FreeCAD internal Python editor through a menu item or a icon on the toolbar area, but knowing that FreeCAD opens a file with a .py extension in the internal Python editor, the most simple trick is create in your favourite text editor and then open it with the usual command File - Open.

To make the things in a polite way, the fila has to be written with some order, FreeCAD Python editor have a good "Syntax HIghlighting" that lacks in many simple editors like Windows Notepad or some basic Linux editors, so it is sufficient to write these few lines:

"""script.py

Primo script per FreeCAD

"""

Save them with a meaningfull name with .py extension and load the resulting file in FreeCAD, with the said File - Open command.

A minimal example of what is necessary to have in a script is shown in this portion of code that you could be use as a template for almost any future script:

"""filename.py

Here a short but significant description of what the script do

"""

import FreeCAD

from FreeCAD import Base, Vector

import Part

from math import pi, sin, cos

DOC = FreeCAD.activeDocument()

DOC_NAME = "Pippo"

def clear_doc():

"""

Clear the active document deleting all the objects

"""

for obj in DOC.Objects:

DOC.removeObject(obj.Name)

def setview():

"""Rearrange View"""

FreeCAD.Gui.SendMsgToActiveView("ViewFit")

FreeCAD.Gui.activeDocument().activeView().viewAxometric()

if DOC is None:

FreeCAD.newDocument(DOC_NAME)

FreeCAD.setActiveDocument(DOC_NAME)

DOC = FreeCAD.activeDocument()

else:

clear_doc()

# EPS= tolerance to use to cut the parts

EPS = 0.10

EPS_C = EPS * -0.5

Some tricks are incorporated in the above code:

import FreeCADThis line import FreeCAD in the FreeCAD Python interpreter, it may seem a redundant thing, but it isn'tfrom FreeCAD import Base, VectorBase and Vector are widely used in FreeCAD scipting, import them in this manner will save you to invoke them withFreeCAD.VectororFreeCAD.Baseinstead ofBaseorVector, this will save many keystrokes and make codelines much smaller.

Let's start with a small script that does a very small job, but display the power of this approach.

def cubo(nome, lung, larg, alt):

obj_b = DOC.addObject("Part::Box", nome)

obj_b.Length = lung

obj_b.Width = larg

obj_b.Height = alt

DOC.recompute()

return obj_b

obj = cubo("test_cube", 5, 5, 5)

setview()

Put these lines after the "template" code and press the green arrow in the Macro toolbar

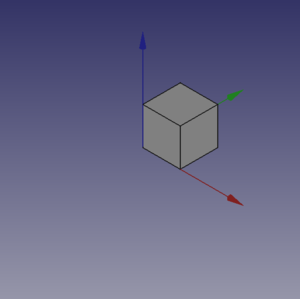

You will see some magic things, a new document is open named "Pippo" (Italian name of Goofy) and you will see in the 3d view a cube, like the one in the image below.

Something more...

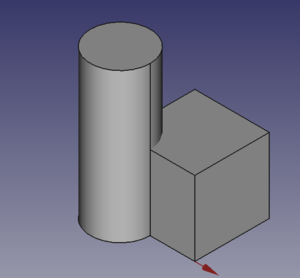

Not too amazing? Yes, but we have to start somewhere, same thing we can do with a Cylinder, add these lines of code after the cubo( method and before the line {{{1}}}.

def base_cyl(nome, ang, rad, alt ):

obj = DOC.addObject("Part::Cylinder", nome)

obj.Angle = ang

obj.Radius = rad

obj.Height = alt

DOC.recompute()

return obj

Even here nothig too exciting. But please note some peculiarities:

- The absence of the usual reference to the

App., present in many Documentation code snippets, is deliberate, this code could be used even invoking FreeCAD as a module in an external Python, the thing is not easily doable with an AppImage, but with some care it could be done. Plus in the standard Python motto that "better explicit than implicit"App.is explaining in a very "poor" way where the things are from. {{{1}}}, note the use of the "constant" name assigned to the active Document, that is not a "constant" in a strict mean, but in a "semantical" way is our "active Document", that four our use is a proper "constant" so the Python convention to use the "ALL CAPS" name for "constants", not to mention thatDOCis much shorten thanFreeCAD.activeDocument().- every method returns a geometry, this became clear in the continuation of the page.

- geometry didn't have the

Placementproperty, when usign the simple geometries to make more complex geometry, managingPlacementis a ankward thing.

Ora dobbiamo pur farci qualcosa con questi oggetti, quindi introduciamo le operazioni booleane. Un esempio di metodo che compie un'operazione di Unione è questo:

def fuse_obj(nome, obj_0, obj_1):

obj = DOC.addObject("Part::Fuse", nome)

obj.Base = obj_0

obj.Tool = obj_1

obj.Refine = True

DOC.recompute()

return obj

anche qui nulla di eccezionale, notate però l'uso di molta uniformità nel codice, aiuta molto quando si vuole fare copia e incolla nella creazioni complesse.

Inseriamo dopo il metodo base_cyl le righe sopra e modifichiamo quelle sotto in modo da leggere:

# definizione oggetti

obj = cubo("cubo_di_prova", 5, 5, 5)

obj1 = base_cyl('primo cilindro', 360,2,10)

fuse_obj("Fusione", obj, obj1)

Lanciamo con il tasto freccia della barra strumenti macro e otteniamo:

Posizionamento

Il concetto è relativamente complesso, vedere il Tutorial aeroplano per una trattazione più sistematica.

Possiamo aver bisogno di posizionare una geometria in una posizione relativa ad un'altra geometria, cosa abbastanza frequente, il modo più comune è usare la proprietà Placement della geometria.

Ovviamente le possibilità su come specificare questa proprietà sono molte, alcune complesse da capire, questa scrittura della proprietà Placement, soprattutto per quanto riguarda la parte Rotation è in linea con quanto spiegato nel Tutorial citato e sembra la più gestibile.

FreeCAD.Placement(Vector(0,0,0), FreeCAD.Rotation(10,20,30), Vector(0,0,0))

Esiste sempre un punto di criticità, che è il punto di riferimento della costruzione, cioè il punto in base al quale è costruito l'oggetto, come descritto in questa tabella, copiata da Posizionamento:

| Geometria | Riferimento di Costruzione |

|---|---|

| Part::Box | vertice sinistro (minimo x), frontale (minimo y), in basso (minimo z) |

| Part::Sphere | centro della sfera (centro del suo contenitore cubico) |

| Part::Cylinder | centro della faccia di base |

| Part::Cone | centro della faccia di base (o superiore se il raggio della faccia di base vale 0) |

| Part::Torus | centro del toro |

| Caratteristiche derivate da Sketch | la caratteristica eredita la posizione dello schizzo sottostante. Lo schizzo inizia sempre con Position = (0,0,0). |

Queste informazioni sono da tenere ben presente quando volete applicare una rotazione.

Facciamo qualche esempio, cancellate tutte le righe dopo il metodo base_cyl ed inserite queste righe:

def sfera(nome, rad):

obj = DOC.addObject("Part::Sphere", nome)

obj.Radius = rad

DOC.recompute()

return obj

def mfuse_obj(nome, objs):

obj = DOC.addObject("Part::MultiFuse", nome)

obj.Shapes = objs

obj.Refine = True

DOC.recompute()

return obj

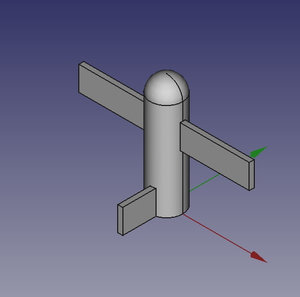

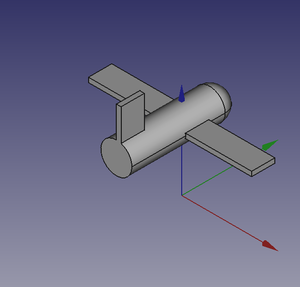

def aeroplano():

lung_fus = 30

diam_fus = 5

ap_alare = lung_fus * 1.75

larg_ali = 7.5

spess_ali = 1.5

alt_imp = diam_fus * 3.0

pos_ali = (lung_fus*0.70)

off_ali = (pos_ali - (larg_ali * 0.5))

obj1 = base_cyl('primo cilindro', 360, diam_fus, lung_fus)

obj2 = cubo('ali', ap_alare, spess_ali, larg_ali, True, off_ali)

obj3 = sfera("naso", diam_fus)

obj3.Placement = FreeCAD.Placement(Vector(0,0,lung_fus), FreeCAD.Rotation(0,0,0), Vector(0,0,0))

obj4 = cubo('impennaggio', spess_ali, alt_imp, larg_ali, False, 0)

obj4.Placement = FreeCAD.Placement(Vector(0,alt_imp * -1,0), FreeCAD.Rotation(0,0,0), Vector(0,0,0))

objs = (obj1, obj2, obj3, obj4)

obj = mfuse_obj("Forma esempio", objs)

obj.Placement = FreeCAD.Placement(Vector(0,0,0), FreeCAD.Rotation(0,0,0), Vector(0,0,0))

obj.Placement = FreeCAD.Placement(Vector(0,0,0), FreeCAD.Rotation(0,0,-90), Vector(0,0,pos_ali))

DOC.recompute()

return obj

aeroplano()

setview()

Analizziamo il codice:

- Abbiamo definito un metodo per creare una sfera, abbiamo usato la definizione più semplice, definendo solo il raggio.

- Abbiamo introdotto una seconda forma per l'Unione quella multipla, niente di speciale, notate solo che alla proprietà

Shapesabbiamo passato una tupla - Abbiamo definito una forma complessa, in modo "parametrico", cioè definendo alcuni parametri e mettendo delle formule che calcolano in modo automatico molti dei valori da passare alla geometria finale.

- Abbiamo usato prima di ritornare l'oggetto un posizionamento usando la poprietà

Rotatione il vettore finale del gruppo che definisce il centro di rotazione, secondo la scrittura Yaw-Pitch-Roll

|

|

|

Potete facilmente notare che l'aereo ruota attorno al suo "baricentro" che ho fissato nel centro delle ali, in modo che la rotazione sia relativamente "naturale".

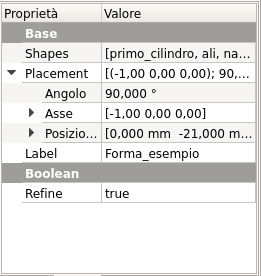

Notiamo però che se usiamo l'interfaccia grafica e visualizziamo la proprietà Placement abbiamo i dati che abbiamo inserito, questo significa che ogni modifica della proprietà modificherà il posizionamento della geometria, l'osservazione sarà importante nel proseguimento del discorso.

Alla prossima!